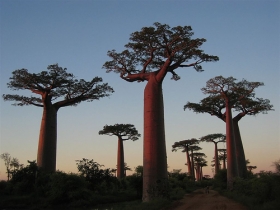

SUKUR, Nigeria (Reuters) - Visitors to Sukur are warned not to approach a certain ancient baobab tree because, villagers say, it turns people into hermaphrodites.

It is an atmospheric introduction to this Nigerian World Heritage Site for the trickle of outsiders who come, but villagers who trek up and down from the remote hillside community are ready for an injection of modernity.

A road would be a start.

SUKUR, Nigeria (Reuters) - Visitors to Sukur are warned not to approach a certain ancient baobab tree because, villagers say, it turns people into hermaphrodites.

It is an atmospheric introduction to this Nigerian World Heritage Site for the trickle of outsiders who come, but villagers who trek up and down from the remote hillside community are ready for an injection of modernity.

A road would be a start.

As the outside world starts to take a greater interest in the hilltop outpost, which earned its World Heritage label from UNESCO in 1999, the people there would also like to see more of the outside world.

"Can you take me to your place?" asked Hadanina Ajesko, 29, joking with a foreign visitor as she bent over to harvest groundnuts from a terraced field, her baby strapped to her back.

A wide gash in the hillside is still visible from where the village men started digging a road before the government of Adamawa state, where Sukur is located, told them to stop.

So the farms and stone dwellings perched in lush mountains near the northeastern border with Cameroon are accessible only by a steep footpath, paved centuries ago with slabs of local granite.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

"I have never been further than Madagali," said Ajesko through a translator, referring to a tiny market town about 15 km (9 miles) away where the women of Sukur sell their produce.

PAST THE BAOBAB TREE

Farmers still terrace the steep slopes to grow millet, groundnuts or beans. Blacksmiths make farming tools in traditional forges powered by manual bellows, high in the hills rich in iron ore.

The Hidi, or king, can resolve disputes and take decisions that affect the whole community, while in his spiritual role he presides over the cult of the ancestors and religious festivals.

His palace is a compound of stone huts with roofs made of woven mats, protected by an ancient circular dry-stone wall. Every corner has a specific function in the annual cycle of festivals celebrating farming, cattle and the ancestors.

Villagers say two giants built the palace in a single night before vanishing.

What makes Sukur special is that its tradition of terracing is for ritual as well as farming purposes, experts say. The terraces incorporate graves and shrines whose layout is strictly codified according to the community's religion and social order.

The footpath winds its way up to the Hidi's palace through fertile terraces, burial grounds and stone gates marking the boundaries of the kingdom, past the perilous baobab tree and its enticing dark green fruit.

While the committee report that recommended Sukur be given World Heritage status hailed its "unusual symbiotic interaction between nature and culture, the dead and the living, the past and the present", the villagers who daily lug heavy loads of water or produce from their farms have had enough.

"Anything we need from outside, we have to carry up the path on our heads, even bags of cement if we want to build something new," said Ezra Ke Bako, 26, a member of the Hidi's family.

Ke Bako returned to Sukur to teach after studying English in a faraway city, but he said more and more young men were leaving for good, moving to Lagos in search of an easier life.

"When someone gets sick, especially a pregnant woman, it's very dangerous because there is no doctor here and we have to carry them down. We make stretchers from branches," he said.

BUILDING A ROAD

The men of Sukur pooled resources and effort last year to start building a road. Villagers said the state government had not explained its decision to halt construction.

A spokesman for the state blamed the previous administration and said the new government was planning to build a road, but he could not say when.

So tourism infrastructure remains limited. A few rusty metal signposts mark the way up the path and around the Hidi's palace, and at the foot of the hill are five simple guest huts, locked up except when visitors come.

The guest book contains about 30 signatures so far this year. Hardly any foreign tourists make it to Nigeria because of its reputation for crime, few Nigerians have heard of Sukur and little practical information is available for those who have.

For Sukur, even that small number of visitors is a break with a past of near-total isolation.

"The main difference to our lives since Sukur became a World Heritage Site is that we see so many tourists now," said the Hidi, 76-year-old Gezik Kanakakaw, who greets all visitors in the shade of a huge tree just outside his palace.

The Hidi said he welcomed the newcomers, just as he would welcome other gifts from the world outside -- a road of course, but also a clinic, and maybe one day, electricity.

"We are always praying for these things to come," he said.

© Reuters2007All rights reserved

addImpression("460316_Next Article");