TAIPEI (Reuters) - From Beijing to Tokyo, Seoul, Hong Kong and Taipei, faced-paced modern life means that tea has little appeal for Asian youth who don't have the patience to wait the 10 minutes it takes to brew tea in the traditional way.

"I don't have any time or relevant tea culture," said Becca Liu, a 25-year-old college graduate in Taipei.

"I'm more curious to know how to make coffee," she added. Determined to restore tea to its exalted status in Asia, tea lovers are trying to repackage tea as a funky new-age brew to a young generation more inclined to slurp down a can of artificially-flavored tea than to sip the real thing.

TAIPEI (Reuters) - From Beijing to Tokyo, Seoul, Hong Kong and Taipei, faced-paced modern life means that tea has little appeal for Asian youth who don't have the patience to wait the 10 minutes it takes to brew tea in the traditional way.

"I don't have any time or relevant tea culture," said Becca Liu, a 25-year-old college graduate in Taipei.

"I'm more curious to know how to make coffee," she added.

Determined to restore tea to its exalted status in Asia, tea lovers are trying to repackage tea as a funky new-age brew to a young generation more inclined to slurp down a can of artificially-flavored tea than to sip the real thing.

Taiwan tea expert Yang Hai-chuan sells sachets of mixed oolong and green tea leaves at teahouses across Taipei, marketing them as hip flavored beverages rather than the traditional teas that have been drunk for centuries.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

"Consumption of traditional tea is declining because it's not being passed down," said Yang, who teaches tea brewing classes to a handful of students such as Liu, who sign up mostly because of the coffee-making section in the course.

"Basically there's no one promoting it."

Yang's concoction is just one around North Asia that's sustaining tea, despite pressure from coffee and other beverages, by catering to younger people's fixations on their health and a thirst for novelty.

In Japan, a new tea line is winning fans among young Japanese with its claims to reduce body fat, while a South Korean brand called "17 Tea" is popular for its claims to blend teas that cure a host of ills.

TURNING OVER A NEW LEAF

According to a Chinese myth, tea was discovered about 5,000 years ago by Shennong, a legendary emperor of China who was sipping a bowl of hot water when a sudden gust of wind blew some tea tree twigs into the water.

The rest as they say is history.

It became a pillar of cultural and culinary life in Asia ever since, spreading to Europe in the 17th century.

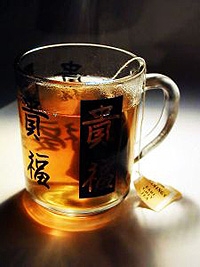

The elaborate tea making ceremonies of past centuries are largely defunct across North Asia, although traditional drinkers avoid Western tea bags and devoutly adhere to tea-making customs by pouring hot water from clay pots over tea leaves.

Teahouses across the region, from airport waiting halls in China to parks and temples in Taiwan, continue the tradition but mostly to the older generation who are willing to pay up to $1 per gram for prime tea leaves.

Younger drinkers prefer canned tea, powdered tea, soft drinks and coffee. They increasingly refer to traditional tea as "old people's drink".

Tea is so embedded in Taiwan culture -- at least for the older generation -- that tea lovers can argue for hours about the merits of tea grades and water temperatures for preparation of the brew.

But Taiwan youngsters won't have a bar of it.

"Our children don't want to carry on the traditions, so in the future it will be forgotten," complained Wang Cheng-long, a life-long bulk leaf seller in Taiwan's historic tea-growing region of Pinglin.

Minoru Takano, director of the Japanese Association of Tea Production, admits that canned flavored teas have helped keep consumption levels up in Japan.

"But we are concerned that tea culture will not be nurtured by these drinks," Takano said.

"We are trying to promote making tea by the pot. There are some households that do not (even) have a pot. We are concerned that the tradition and culture may disappear."

(Additional reporting by Jessica Kim in Seoul and Taiga Uranaka in Tokyo)

© Reuters2007All rights reserved