Redrawing the global map of crop distribution on existing farmland could help meet growing demand for food and biofuels in coming decades, while significantly reducing water stress in agricultural areas, according to a new study. Published today in Nature Geoscience, the study is the first to attempt to address both food production needs and resource sustainability simultaneously and at a global scale.

Redrawing the global map of crop distribution on existing farmland could help meet growing demand for food and biofuels in coming decades, while significantly reducing water stress in agricultural areas, according to a new study. Published today in Nature Geoscience, the study is the first to attempt to address both food productionneeds and resource sustainability simultaneously and at a global scale.

The results show that “there are a lot of places where there are inefficiencies in water use and nutrient production,” says lead author Kyle Davis, a postdoctoral researcher with Columbia University’s Earth Institute. Those inefficiencies could be fixed, he says, by swapping in crops that have greater nutritional quality and lower environmental impact.

Agricultural demand is forecasted to grow substantially over the next few decades due to population growth, richer diets, and biofuel use. Meanwhile, water stress is expected to worsen with climate change and as global aquifers are rapidly depleted. In an attempt to address these twin challenges, the authors looked at crop water-use models and yield maps for 14 major food crops. They were specifically interested in identifying crop distributions that would make rain-fed production less susceptible to dry spells and reduce water consumption in irrigated systems.

The researchers chose to focus on 14 crops that make up 72 percent of all crops harvested around the world: groundnut, maize, millet, oil palm, rapeseed, rice, roots, sorghum, soybean, sugar beet, sugarcane, sunflowers, tubers and wheat. Fruits and vegetables were not included because good data on their water requirements were not available.

Read more at The Earth Institute at Columbia University

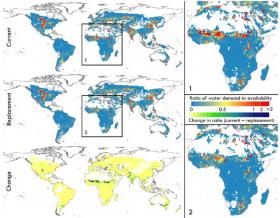

Image: Rearranging where crops are grown could feed more people while reducing water scarcity. (Credit: Davis et al., Nature Geoscience 2017)