The living, breathing ocean may be slowly starting to suffocate. More than two percent of the ocean’s oxygen content has been depleted during the last half century, according to reports, and marine “dead zones” continue to expand throughout the global ocean. This deoxygenation, triggered mainly by more fertilizers and wastewater flowing into the ocean, pose a serious threat to marine life and ecosystems.

Yet despite the critical role of oxygen in the ocean, scientists haven’t had a way to measure how fast deoxygenation occurs—today, or in the past when so-called major “anoxic events” led to catastrophic extinction of marine life.

The living, breathing ocean may be slowly starting to suffocate. More than two percent of the ocean’s oxygen content has been depleted during the last half century, according to reports, and marine “dead zones” continue to expand throughout the global ocean. This deoxygenation, triggered mainly by more fertilizers and wastewater flowing into the ocean, pose a serious threat to marine life and ecosystems.

Yet despite the critical role of oxygen in the ocean, scientists haven’t had a way to measure how fast deoxygenation occurs—today, or in the past when so-called major “anoxic events” led to catastrophic extinction of marine life.

Now, researchers at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Arizona State University, and Florida State University have, for the first time, developed a way to quantify how fast deoxygenation occurred in ancient oceans. The research was published Aug. 9, 2017, in the journal Science Advances.

“To date, there haven’t been quantitative tools available to scientists that are capable of accurately measuring the rate at which oxygen depletion happens,” said Sune Nielsen, WHOI scientist and co-author of the paper. “Can the ocean lose half its oxygen in a thousand years? This new tool will help us understand the rate at which deoxygenation was happening in the past, and eventually estimate how far present-day losses might extend into the future.”

Continue reading at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

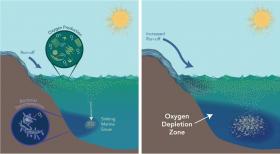

Illustration: An influx of nutrients to the ocean—catalyzed by higher temperatures—stimulates organic matter production and subsequent decomposition, consuming oxygen in the process. This is thought to be primarily responsible for large-scale oxygen loss in ancient oceans, leading to mass extinctions in the marine environment. Unfortunately, the modern ocean is exhibiting similar symptoms.

Credit: Natalie Renier, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution