Tracking mobile phone data is often associated with privacy issues, but these vast datasets could be the key to understanding how infectious diseases are spread seasonally, according to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Princeton University and Harvard University researchers used anonymous mobile phone records for more than 15 million people to track the spread of rubella in Kenya and were able to quantitatively show for the first time that mobile phone data can predict seasonal disease patterns.

Harnessing mobile phone data in this way could help policymakers guide and evaluate health interventions like the timing of vaccinations and school closings, the researchers said. The researchers' methodology also could apply to a number of seasonally transmitted diseases such as the flu and measles.

Tracking mobile phone data is often associated with privacy issues, but these vast datasets could be the key to understanding how infectious diseases are spread seasonally, according to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Princeton University and Harvard University researchers used anonymous mobile phone records for more than 15 million people to track the spread of rubella in Kenya and were able to quantitatively show for the first time that mobile phone data can predict seasonal disease patterns.

Harnessing mobile phone data in this way could help policymakers guide and evaluate health interventions like the timing of vaccinations and school closings, the researchers said. The researchers' methodology also could apply to a number of seasonally transmitted diseases such as the flu and measles.

"One of the unique opportunities of mobile phone data is the ability to understand how travel patterns change over time," said lead author C. Jessica Metcalf, assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and public affairs at Princeton's Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. "And rubella is a well-known seasonal disease that has been hypothesized to be driven by human population dynamics, making it a good system for us to test."

"The potential of mobile phone data for quantifying mobility patterns has only been appreciated in the last few years, with methods pioneered by authors on this paper," said lead author Amy Wesolowski, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard's School of Public Health. "It is a natural extension to look at seasonal travel using these data."

In the past, it was difficult to collect data on individuals in low-income and undeveloped countries due to a lack of technology usage. But mobile phone ownership, especially in these areas, is rapidly increasing, producing large and complex datasets on millions of people. Because of the mobility of cellphones, it is possible that phone records could predict certain health-related patterns. This spurred the researchers to take a closer look.

Ultimately, the research team wanted to see whether cellphone users and their movement around the country could predict the seasonal spread of rubella. The researchers used available records to analyze mobile phone usage and movement between June 2008 and June 2009 for more than 15 million cellphone users in Kenya. (Note: February 2009 was missing from the dataset.)

Using the location of the routing tower and the timing of each call and text message, the researchers were able to determine a daily location for each user as well as the number of trips these users took between the provinces each day. In total, more than 12 billion mobile phone communications were recorded anonymously and linked to a province.

The researchers then compared the cellphone analysis with a highly detailed dataset on rubella incidence in Kenya. They matched; the cellphone movement patterns lined up with the rubella incidence figures. In both of their analyses, rubella spiked three times a year: September and February primarily, and, in a few locations, rubella peaked again in May. This showed the researchers that cellphone movement can be a predictor of infectious-disease spread.

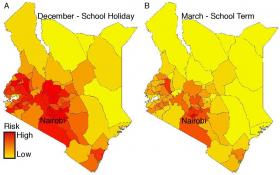

Using mobile phone data, the researchers constructed these maps to characterize rubella fluxes across the country. Section A shows the risk of rubella during a major holiday and school term break. Section B shows the risk of rubella while school is in session. Most provinces have lower risks during the school year with higher outbreak rates during breaks and holidays. (Photo courtesy of Amy Wesolowski, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; and C. Jessica Metcalf, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University)

Read more at Princeton University.