WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Researchers have found more than 200 possible new targets for better AIDS drugs by doing a kind of backward search -- looking at human cells to see what resources they have that can be hijacked by the deadly virus.

By Maggie Fox, Health and Science Editor

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Researchers have found more than 200 possible new targets for better AIDS drugs by doing a kind of backward search -- looking at human cells to see what resources they have that can be hijacked by the deadly virus.

They scanned all the genes in the human genome and found 273 protein-coding genes that the human immunodeficiency virus uses to infect cells and propagate itself.

Many could provide the basis for new drugs, said Dr. Stephen Elledge of Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, who led the study.

!ADVERTISEMENT!"It should spur a lot of research (and provide) new and novel ideas about how to thwart this virus," Elledge said in a telephone interview.

"Some drug companies have done these sorts of screens but they didn't make this information public."

Elledge, whose study appears in Friday's issue of the journal Science, said it is possible some of the drugs that may result from the work will be harder, if not impossible, for the virus to develop resistance to.

HIV only has nine genes, so like other viruses, it must rely on its victims' cells to replicate itself.

The virus uses its nine genes and the 15 proteins they code for to first attach to a cell, get inside it, find the nucleus that contains the DNA, get in there, and hijack the DNA. It turns the cell into a virus factory, pumping out copies of itself until the cell dies.

These new virus copies then travel through the body to find more cells.

The 20 or so HIV drugs on the market target various stages of this process. But they cannot completely suppress the virus and it eventually develops resistance, meaning the drugs no longer work. That is why there is no cure for HIV.

NEW TACK AGAINST AIDS

Elledge's team used two new approaches to try to find better ways to understand and fight HIV. First, they looked at the entire human genome, instead of looking at the virus.

They used a new method called small interfering RNAs or siRNAs. The discovery of RNA interference won the 2006 Nobel Prize in medicine for Andrew Fire of Stanford University and Craig Mello at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

DNA carries the genetic code of an organism. RNA is the genetic material used to translate this code into something a cell can actually use to do something.

Small interfering RNAs are bits of this material. "It is specialized to interfere with one particular gene," Elledge said.

"You can take away a gene from a cell one at a time and say 'what does it do?' This way you sort of trick the cell into revealing its secrets."

Using a robotic lab, Elledge's team used this method to one by one take away a single gene from cells -- more than 21,000 times for the 21,000-plus genes in the human genome.

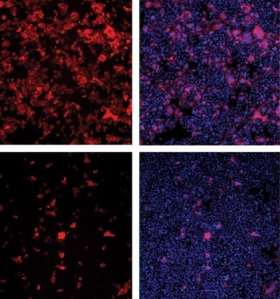

Then they squirted some HIV into a lab dish with each cell with its missing gene. "And we wait a day and a half or so and look to see how well HIV multiplied in those cells," Elledge said.

For most of the 273 genes they found, no one had a clue they were involved in AIDS. "About half of them probably were things that I personally was familiar with from studying cell biology," Elledge said.

"There were a whole bunch of genes that we don't know what they are doing."

Current drugs affect the virus directly. But drugs that affect human proteins will be more complex and far more difficult for the virus to evade, he said.

"The virus would not be able to mutate to overcome drugs that interact with these proteins," he said.

(Reporting by Maggie Fox; Editing by Xavier Briand)