LONDON (Reuters) - Scientists have found important genetic differences between people that may help explain why some smokers get lung cancer and others do not.

By Ben Hirschler

LONDON (Reuters) - Scientists have found important genetic differences between people that may help explain why some smokers get lung cancer and others do not.

Three teams from France, Iceland and the United States said on Wednesday they had pinpointed a region of the genome containing genes that can put smokers at even greater risk of contracting the killer disease.

In all three studies, nicotine appears a major culprit.

!ADVERTISEMENT!The findings could eventually lead to better ways to prevent and treat lung cancer, the biggest cause of cancer-related death globally in men and the second most common in women.

"It opens the possibility that treatments that block these genes could be very beneficial as a treatment strategy against lung cancer, as well as against addiction," Paul Brennan of the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, told reporters.

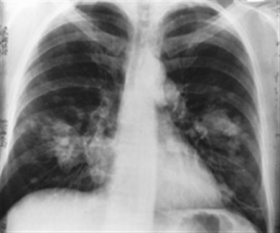

Smoking causes nine out of 10 cases of lung cancer. Yet only about 15 percent of smokers actually develop the condition and doctors have long suspected that a genetic element is involved.

The new research confirms some smokers are indeed more vulnerable because of their DNA profile. Smokers with two copies of the genetic variations stand around a 23 percent risk of lung cancer, according to Brennan.

The findings mark another step in unraveling the genetic basis of diseases by analyzing common changes in the genetic code known as single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs (pronounced "snips).

Since early 2007, variations at nearly 100 places on the genome have been linked to diabetes, heart disease and certain cancers.

NICOTINE'S ROLE

Significantly, all three groups publishing results in Nature and Nature Genetics zeroed in on tell-tale variants in the same area of chromosome 15 that hosts three nicotine receptor genes.

That might suggest nicotine itself is carcinogenic as well as addictive. Alternatively, it could simply be that some people are more likely to get addicted to cigarettes and smoke more, thereby exposing their lungs to greater damage.

"We need to get a better handle on how genetic factors increase risk and what molecular pathways are involved in development of lung cancer," said Chris Amos at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Kari Stefansson, the chief executive of Iceland's Decode Genetics Inc, whose scientists conducted the third study and which sells tests to assess risks for other diseases, was cautious about the value of screening for the new DNA traits.

"This is the first step in understanding what sequence variants lie behind lung cancer and nicotine addiction," he said.

Other researchers also warned personalized testing could weaken the public health message that everyone should quit smoking. Even if some people have a degree of resistance to lung cancer, they will still likely be vulnerable to smoking-related heart disease and serious respiratory disorders.

Smoking is also the leading cause of heart disease, the number one killer in the developed world, and emphysema.

(Editing by Maggie Fox and Matthew Jones)