The Seven Sisters, as they were known to the ancient Greeks, are now known to modern astronomers as the Pleiades star cluster – a set of stars which are visible to the naked eye and have been studied for thousands of years by cultures all over the world. Now Dr Tim White of the Stellar Astrophysics Centre at Aarhus University and his team of Danish and international astronomers have demonstrated a powerful new technique for observing stars such as these, which are ordinarily far too bright to look at with high performance telescopes. Their work is published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The Seven Sisters, as they were known to the ancient Greeks, are now known to modern astronomers as the Pleiades star cluster – a set of stars which are visible to the naked eye and have been studied for thousands of years by cultures all over the world. Now Dr Tim White of the Stellar Astrophysics Centre at Aarhus University and his team of Danish and international astronomers have demonstrated a powerful new technique for observing stars such as these, which are ordinarily far too bright to look at with high performance telescopes. Their work is published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Using a new algorithm to enhance observations from the Kepler Space Telescope in its K2 Mission, the team has performed the most detailed study yet of the variability of these stars. Satellites such as Kepler are engineered to search for planets orbiting distant stars by looking for the dip in brightness as the planets pass in front, and also to do asteroseismology, studying the structure and evolution of stars as revealed by changes in their brightness.

Because the Kepler mission was designed to look at thousands of faint stars at a time, some of the brightest stars are actually too bright to observe. Aiming a beam of light from a bright star at a point on a camera detector will cause the central pixels of the star's image to be saturated, which causes a very significant loss of precision in the measurement of the total brightness of the star. This is the same process which causes a loss of dynamic range on ordinary digital cameras, which cannot see faint and bright detail in the same exposure.

Read more at Royal Astronomical Society

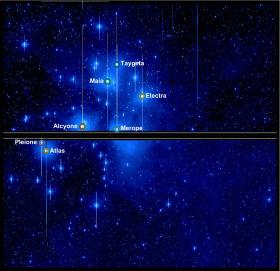

Image: This image from NASA's Kepler spacecraft shows members of the Pleiades star cluster taken during Campaign 4 of the K2 Mission. The cluster stretches across two of the 42 charge-coupled devices (CCDs) that make up Kepler's 95 megapixel camera. The brightest stars in the cluster -- Alcyone, Atlas, Electra, Maia, Merope, Taygeta, and Pleione -- are visible to the naked eye. Kepler was not designed to look at stars this bright; they cause the camera to saturate, leading to long spikes and other artifacts in the image. Despite this serious image degradation, the new technique has allowed astronomers to carefully measure changes in brightness of these stars as the Kepler telescope observed them for almost three months. (Credit: NASA / Aarhus University / T. White)