LONDON (Reuters) - Turning off a sex "switch" triggered when female insects mate may be a smart and green way of controlling pests in future.

LONDON (Reuters) - Turning off a sex "switch" triggered when female insects mate may be a smart and green way of controlling pests in future.

Scientists said on Sunday they had found a molecular receptor, or switch, common to all insects that sets off post-mating behaviors like egg-laying.

Developing a chemical to artificially block its action could stop insect populations in their tracks and help fight the spread of many human and animal diseases.

!ADVERTISEMENT!"If you had an inhibitor of this receptor then you could interfere with its function and it would, in effect, be a birth control pill for insects," said Barry Dickson from the Institute of Molecular Pathology in Vienna, Austria.

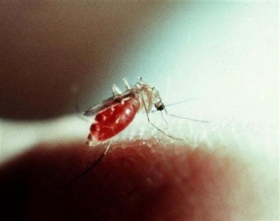

Many female insects undergo profound changes in behavior after mating. Some species start laying multiple eggs. Female mosquitoes, for example, seek out a meal of blood -- often spreading malaria in the process.

Scientists have known for some time that such behavior is triggered by a so-called sex peptide molecule in the male's seminal fluid, but it has been unclear how it exerts its impact on the female.

Now Dickson and his colleagues have identified the receptor for the molecule in fruit flies and shown it is key to post-mating behavior. Females lacking the receptor continue to behave as virgins, even after mating, they reported in the journal Nature.

Crucially, the same receptor has been found in all insects studied so far, suggesting it may be possible to develop a widely applicable chemical blocker that would be far more effective and environmentally friendly than insecticides.

Modern insecticides are good at killing bugs, but because insects breed so prolifically, those that die are quickly replaced.

By contrast, females dosed with a sex peptide receptor blocker would remain alive and continue to compete in the breeding pool, producing a bigger impact on the wider population.

Developing the concept will require a lot more research but Dickson said it was possible such a blocker might be introduced into breeding ponds where larvae grow or else planted in pheromone traps designed to attract insects.

(Reporting by Ben Hirschler; Editing by Caroline Drees)