One car gets 46 miles per gallon, features fancy accessories, and sports two engines with a combined 145 horsepower. The other car reportedly gets 54 miles per gallon, runs on a diminutive 30-horsepower engine, and is positively spartan in its interior trimmings. The first is a darling of the environmentally conscious. The latter is reviled as a climate wrecker. These two vehicles are the Toyota Prius and the newly unveiled Tata Nano, dubbed “the people’s car.†Is there a double standard?

One car gets 46 miles per gallon, features fancy accessories, and sports two engines with a combined 145 horsepower. The other car reportedly gets 54 miles per gallon, runs on a diminutive 30-horsepower engine, and is positively spartan in its interior trimmings. The first is a darling of the environmentally conscious. The latter is reviled as a climate wrecker. These two vehicles are the Toyota Prius and the newly unveiled Tata Nano, dubbed “the people’s car.†Is there a double standard?

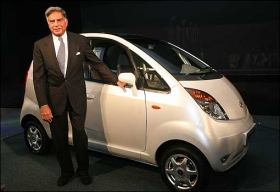

Advertised as the world’s cheapest car, the Nano is a no-frills automobile designed by Indian conglomerate Tata to be affordable for millions, possibly hundreds of millions, of people who are newly joining the middle class in India and elsewhere in the developing world. Such mass sales might overwhelm halting efforts to ward off catastrophic climate change. As Indians (and others) join the love affair with the private automobile, many in the West are suddenly aghast at the prospect of Nano becoming a household term like Chevy or Mercedes. The German weekly Der Spiegel termed it an “eco-disaster.â€

Indeed, transportation has the fastest growing carbon emissions of any economic sector. Proliferating numbers of automobiles are a key reason. More than 600 million passenger cars are now on the world’s roads, and each year some 67 million new ones roll out of manufacturing plants.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

But amid the finger pointing, let’s remember who has driven the planet to the edge of the climate abyss. People in Western countries and Japan—less than 15 percent of the world’s population—own two-thirds of all passenger and commercial motor vehicles in the world. Although they are rapidly expanding their fleets, India and China, with a third of the world’s population, so far account for only about 5 percent of vehicles. In 2005, China’s ratio of motor vehicles to population was at about the level the United States had reached some 90 years earlier. India’s ratio is less than half that of China.

Westerners not only have far more cars, but the distances they drive are also 3–4 times longer on average than those of Indians and Chinese. The United States alone—where monster SUVs roam and driving is considered a birthright—claims about 44 percent of the world’s gasoline consumption. Fuel economy has stagnated for a quarter-century as cars grew larger, heavier, and more muscular. Here in New York, a Nano might be mistaken for a golf cart.

So if it’s true that Asia’s (and Latin America’s and Africa’s) teeming billions can’t indulge in the same reckless habits as Westerners, then neither can Americans, Europeans, or Japanese. Delhi and Beijing know hypocrisy when they encounter it. Nonetheless, they have good reason to take action irrespective of what Western countries say or do. Residents of many Asian cities are exposed to a lethal brew of sulfur and nitrogen oxides, particulates, and toxics from motor vehicles of all stripes. Breathable air is every bit as important as climate stability.

Leaner engines and cleaner fuels are essential. The Nano may well be a cleaner option than the highly polluting motorcycles, motor rickshaws, and diesel buses (and many of the Western-designed cars) already clogging India’s roads. But the mass market that Tata is hoping for will render putative gains ephemeral.

All countries need to seriously rethink their transportation policies. Such an effort has to go far beyond the pursuit of alternative fuels and even beyond making cars more efficient. Denser cities and shorter distances reduce the overall need for motorized transportation and make public transit, biking, and walking more feasible. Those who will never be able to afford a car will have more options instead of being marginalized by the onslaught of private automobiles.

In a BBC World Service call-in debate, Malini Mehra, founder of the Centre for Social Markets in Kolkata, India, questioned those who regard car ownership a right. And Sunita Narain, head of India’s Centre for Science and Environment, has pointed out that private motor vehicles “are providing transport only to 20 percent of people in Delhi.†She called on Tata and other manufacturers to “provide solutions for public transport.â€

The change needed is more than a matter of technology. It requires questioning shortsighted personal choices by consumers who buy unnecessarily large or powerful vehicles, as well as confronting the auto and oil companies that derive enormous profit from the status quo.