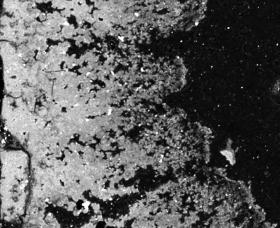

A study of lead service lines in Flint's damaged drinking water system reveals a Swiss cheese pattern in the pipes' interior crust, with holes where the lead used to be.

The findings—led by researchers at the University of Michigan—support the generally accepted understanding that lead leached into the system because that water wasn't treated to prevent corrosion. While previous studies had pointed to this mechanism, this is the first direct evidence. It contradicts a regulator's claim earlier this year that corrosion control chemicals would not have prevented the water crisis.

A study of lead service lines in Flint's damaged drinking water system reveals a Swiss cheese pattern in the pipes' interior crust, with holes where the lead used to be.

The findings—led by researchers at the University of Michigan—support the generally accepted understanding that lead leached into the system because that water wasn't treated to prevent corrosion. While previous studies had pointed to this mechanism, this is the first direct evidence. It contradicts a regulator's claim earlier this year that corrosion control chemicals would not have prevented the water crisis.

Researchers say the findings underscore how important uninterrupted anti-corrosion treatment is for the aging water systems that serve millions of American homes.

The team focused on the layer of metal scale—essentially lead rust—inside 10 lead service line samples from around Flint. They studied the texture of the rust layer, as well as its chemical composition. Then they used their analysis to estimate that the average lead service line released 18 grams of lead during the 17 months that Flint river water (without corrosion control) flowed through the system.

Continue reading at University of Michigan

Image: Back scattered electron images of a cross-section of the layer of metal scale, or rust, inside pipe samples from lead service lines in Flint, Michigan. The outside of the pipe is on the left side, and the holes in the “Swiss cheese pattern” are voids where the lead used to be, say researchers at the University of Michigan College of Engineering. Untreated, corrosive water caused the lead to leach out, leaving behind a mineral skeleton of aluminum and magnesium. Credit: Brian Ellis