It’s tempting to believe that the devastating sequence of hurricanes in the Atlantic this year has blown in a new awareness of the risks of rising waters and increasingly powerful storms on our rapidly warming planet. In a rational world, the destruction wrought by these storms would inspire us to redouble our efforts to cut carbon pollution as quickly as possible and begin planning for an orderly retreat to higher ground.

It’s tempting to believe that the devastating sequence of hurricanes in the Atlantic this year has blown in a new awareness of the risks of rising waters and increasingly powerful storms on our rapidly warming planet. In a rational world, the destruction wrought by these storms would inspire us to redouble our efforts to cut carbon pollution as quickly as possible and begin planning for an orderly retreat to higher ground.

But with a few exceptions, that’s not happening. Instead, we’re hunkering down in our SUVs and building walls. Sea walls are going up all over the East and Gulf coasts, and engineers and urban planners are musing about larger barriers that could, in theory, protect entire cities. In Texas, where Hurricane Harvey ravaged Houston in August, a $15 billion project known as the Ike Dike, which would create 55 miles of sand dunes and sea walls around Galveston Bay, is being proposed, as well as an 800-foot wide retractable barrier at the mouth of the Galveston shipping channel. In New York, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has long had plans for a similar barrier around Jamaica Bay to protect vulnerable neighborhoods nearby. In Boston, a city-sponsored report last year recommended considering a barrier across the outer harbor. And this is not an America-only trend. Even in water-friendly European cities like Copenhagen, walling off the harbor is seen by some urban planners as inevitable.

Read more at Yale Environment 360

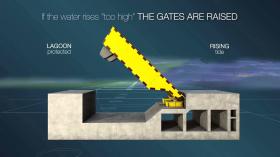

Image: One piece of the MOSE system. Assembled in a line, the barriers rise and fall as water levels change, keeping storm surges and peak high tides from reaching Venice. CREDIT: CONSORZIO VENEZIA NUOVA