SYDNEY (Reuters) - Australian scientists unveiled on Thursday the fossilized remains of the oldest vertebrate mother ever discovered, a 375-million-year-old placoderm fish with embryo and umbilical cord attached.

By Michael Perry

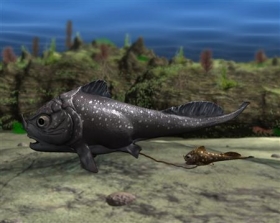

SYDNEY (Reuters) - Australian scientists unveiled on Thursday the fossilized remains of the oldest vertebrate mother ever discovered, a 375-million-year-old placoderm fish with embryo and umbilical cord attached.

The fossil, found in the Gogo area of northwest Australia, is proof that an ancient species had advanced reproductive biology, comparable to modern sharks and rays, said John Long, head of sciences at the Museum of Victoria in Melbourne.

"It is not only the first time ever that a fossil embryo has been found with an umbilical cord, but it is also the oldest known example of any creature giving birth to live young," Long told Reuters.

!ADVERTISEMENT!"It dawned on me after studying the specimen that this was the earliest evidence of vertebrates having sex by copulation, not just spawning in water," Long said.

"This is the first bit of evidence on how a complete extinct class of animals may have reproduced."

The placoderms, often referred to as "the dinosaurs of the seas," were the rulers of the world's lakes and seas for almost 70 million years. Most species of the armored fish were quite small but some reached over 20 feet in length.

Placoderms are from the late Devonian period when land animals evolved from fish.

"This discovery changes our understanding of the evolution of vertebrates," Long said. "It will make us rethink the early evolution of vertebrate in terms of how reproduction has driven evolutionary events."

Long said little was known about how reproductive changes from spawning eggs to internal fertilization affected the evolution species.

The scientists have published their finding in the latest Nature journal (http://www.nature.com/nature).

"The new specimen, remarkably preserved in three dimensions, contains a single, intra-uterine embryo connected by a permineralized umbilical cord. An amorphous crystalline mass near the umbilical cord possibly represents the recrystallized yolk sac," wrote the scientists.

They said the discovery extended internal fertilization and viviparity (giving birth to live young) in vertebrates back by some 200 million years.

"Unlike most other fish that lay eggs in the water...(the) eggs were fertilized internally, the mother provided nourishment to the embryo and gave birth to live young, much like mammals do today," said Kate Trinajstic from the University of Western Australia and co-author of the Nature article.

The Australian scientists have named their 25-cm fossil, Materpiscis attenboroughi, in honor of Sir David Attenborough, who first drew attention to the Gogo fish sites in the 1979 series Life on Earth. The fossil will go on display in the foyer of Melbourne Museum from May 29.

(Editing by Jeremy Laurence)