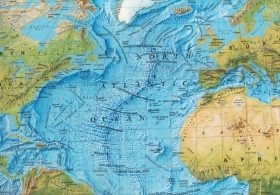

ScienceDaily (Mar. 9, 2011) — The ocean traps carbon through two principal mechanisms: a biological pump and a physical pump linked to oceanic currents. A team of researchers from CNRS, IRD, the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, UPMC and UBO (1) have managed to quantify the role of these two pumps in an area of the North Atlantic. Contrary to expectations, the physical pump in this region could be nearly 100 times more powerful on average than the biological pump. By pulling down masses of water cooled and enriched with carbon, ocean circulation thus plays a crucial role in deep carbon sequestration in the North Atlantic.

ScienceDaily (Mar. 9, 2011) — The ocean traps carbon through two principal mechanisms: a biological pump and a physical pump linked to oceanic currents. A team of researchers from CNRS, IRD, the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, UPMC and UBO (1) have managed to quantify the role of these two pumps in an area of the North Atlantic. Contrary to expectations, the physical pump in this region could be nearly 100 times more powerful on average than the biological pump. By pulling down masses of water cooled and enriched with carbon, ocean circulation thus plays a crucial role in deep carbon sequestration in the North Atlantic.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

These results are published in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

The ocean traps around 30% of the carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere through human activity and represents, with the terrestrial biosphere, the main carbon sink. Much research has been devoted to understanding the natural mechanisms that regulate this sink. On the one hand, there is the biological pump: the carbon dioxide dissolved in the water is firstly used for the photosynthesis of phytoplankton, microscopic organisms that proliferate in the upper layer of the ocean. The food chain then takes over: the phytoplankton is eaten by zooplankton, itself consumed by larger organisms, and so on. Cast into the depths in the form of organic waste, some of this carbon ends its cycle in sediments at the bottom of the oceans. This biological pump is particularly effective in the North Atlantic, where a spectacular bloom of phytoplankton occurs every year. On the other hand, there is the physical pump which, through oceanic circulation, pulls down surface waters containing dissolved carbon dioxide towards deeper layers, thereby isolating the gas from exchanges with the atmosphere.

On the basis of data collected in a specific region of the North Atlantic during the POMME (2) campaigns, the researchers were able to implement high-resolution numerical simulations. They thus carried out the first precise carbon absorption budget of the physical and biological pumps. They succeeded, for the first time, in quantifying the respective proportions of each of the two mechanisms. Surprisingly, their results suggest that in this region of the North Atlantic the biological pump would only absorb a minute proportion of carbon, around one hundredth. The carbon would thus be trapped mainly by the physical pump, which is almost one hundred times more efficient. At this precise location, oceanic circulation pulls down the carbon, in dissolved organic and inorganic form, to depths of between 200 and 400 meters, together with the water masses formed at the surface.

Article continues: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/03/110309132015.htm