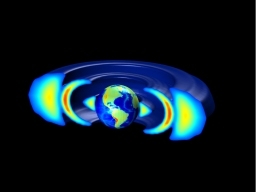

The Earth is circled by belts of electrons and ions that have been the subject of study for decades. Now, a new study casts light on details of these radiation belts that eluded scientists. Since the discovery of the Van Allen radiation belts in 1958, space scientists have believed these belts encircling the Earth consist of two doughnut-shaped rings of highly charged particles — an inner ring of high-energy electrons and energetic positive ions and an outer ring of high-energy electrons. In February of this year, a team of scientists reported the surprising discovery of a previously unknown third radiation ring — a narrow one that briefly appeared between the inner and outer rings in September 2012 and persisted for a month.

The Earth is circled by belts of electrons and ions that have been the subject of study for decades. Now, a new study casts light on details of these radiation belts that eluded scientists.

Since the discovery of the Van Allen radiation belts in 1958, space scientists have believed these belts encircling the Earth consist of two doughnut-shaped rings of highly charged particles — an inner ring of high-energy electrons and energetic positive ions and an outer ring of high-energy electrons.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

In February of this year, a team of scientists reported the surprising discovery of a previously unknown third radiation ring — a narrow one that briefly appeared between the inner and outer rings in September 2012 and persisted for a month.

In new research, UCLA space scientists have successfully modeled and explained the unprecedented behavior of this third ring, showing that the extremely energetic particles that made up this ring, known as ultra-relativistic electrons, are driven by very different physics than typically observed Van Allen radiation belt particles. The region the belts occupy — ranging from about 1,000 to 50,000 kilometers above the Earth's surface — is filled with electrons so energetic they move close to the speed of light.

"In the past, scientists thought that all the electrons in the radiation belts around the Earth obeyed the same physics," said Yuri Shprits, a research geophysicist with the UCLA Department of Earth and Space Sciences. "We are finding now that radiation belts consist of different populations that are driven by very different physical processes."

Shprits, who is also an associate professor at Russia's Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, a new university co-organized by MIT, led the study, which is published Sept. 22 in the journal Nature Physics.

The Van Allen belts can pose a severe danger to satellites and spacecraft, with hazards ranging from minor anomalies to the complete failure of critical satellites. A better understanding of the radiation in space is instrumental to protecting people and equipment, Shprits said.

Image credit UCLA.

Read more at UCLA.