Amphibians can evolve increased tolerance to pesticides, but the adaptation can make them more susceptible to parasites, according to a team that includes researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. The research, led by Binghamton University, showed that wood frogs that evolved increased tolerance to pesticides showed greater susceptibility to a dangerous virus, although they also demonstrated reduced susceptibility to a parasitic worm.

“We have only recently begun to understand that amphibians can rapidly evolve tolerance to chemicals like pesticides, which on the surface is good news,” said Rick Relyea, a professor of biological sciences and director of the Darrin Fresh Water Institute at Rensselaer. “But now comes the bad news: with that tolerance there is a tradeoff, which is that they become more susceptible to parasites that, in the case of ranavirus, can wipe out entire amphibian populations.”

>> Read the Full Article

Last week, researchers at Sandia National Laboratories flew a tethered balloon and an unmanned aerial system, colloquially known as a drone, together for the first time to get Arctic atmospheric temperatures with better location control than ever before. In addition to providing more precise data for weather and climate models, being able to effectively operate UASs in the Arctic is important for national security.

“Operating UASs in the remote, harsh environments of the Arctic will provide opportunities to harden the technologies in ways that are directly transferable to the needs of national security in terms of robustness and reliability,” said Jon Salton, a Sandia robotics manager. “Ultimately, integrating the specialized operational and sensing needs required for Arctic research will transfer to a variety of national security needs.”

>> Read the Full Article

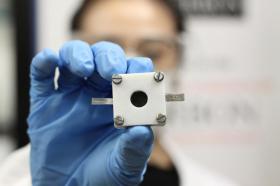

Battery researchers agree that one of the most promising possibilities for future battery technology is the lithium-air (or lithium-oxygen) battery, which could provide three times as much power for a given weight as today’s leading technology, lithium-ion batteries. But tests of various approaches to creating such batteries have produced conflicting and confusing results, as well as controversies over how to explain them.

Now, a team at MIT has carried out detailed tests that seem to resolve the questions surrounding one promising material for such batteries: a compound called lithium iodide (LiI). The compound was seen as a possible solution to some of the lithium-air battery’s problems, including an inability to sustain many charging-discharging cycles, but conflicting findings had raised questions about the material’s usefulness for this task. The new study explains these discrepancies, and although it suggests that the material might not be suitable after all, the work provides guidance for efforts to overcome LiI’s drawbacks or find alternative materials.

>> Read the Full Article

University of Sydney researchers have found a solution for one of the biggest stumbling blocks preventing zinc-air batteries from overtaking conventional lithium-ion batteries as the power source of choice in electronic devices.

Zinc-air batteries are batteries powered by zinc metal and oxygen from the air. Due to the global abundance of zinc metal, these batteries are much cheaper to produce than lithium-ion batteries, and they can also store more energy (theoretically five times more than that of lithium-ion batteries), are much safer, and are more environmentally friendly.

>> Read the Full Article

The approach could revolutionise regenerative medicine, enabling the production of complex tissues and cartilage that would potentially support, repair or augment diseased and damaged areas of the body.

Printing high-resolution living tissues is hard to do, as the cells often move within printed structures and can collapse on themselves. But, led by Professor Hagan Bayley, Professor of Chemical Biology in Oxford’s Department of Chemistry, the team devised a way to produce tissues in self-contained cells that support the structures to keep their shape.

>> Read the Full Article

To help plants better fend off insect pests, researchers are considering arming them with stones.

The University of Delaware’s Ivan Hiltpold and researchers from the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment at Western Sydney University in Australia are examining the addition of silicon to the soil in which plants are grown to help strengthen plants against potential predators.

The research was published recently in the journal Soil Biology and Biochemistry and was funded by Sugar Research Australia. Adam Frew, currently a postdoctoral research fellow at the Charles Sturt University in Australia, is the lead author on the paper.

>> Read the Full Article

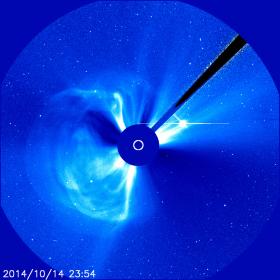

Our Sun is active: Not only does it release a constant stream of material, called the solar wind, but it also lets out occasional bursts of faster-moving material, known as coronal mass ejections, or CMEs. NASA researchers wish to improve our understanding of CMEs and how they move through space because they can interact with the magnetic field around Earth, affecting satellites, interfering with GPS signals, triggering auroras, and — in extreme cases — straining power grids.

>> Read the Full Article

Harmful algal blooms known to pose risks to human and environmental health in large freshwater reservoirs and lakes are projected to increase because of climate change, according to a team of researchers led by a Tufts University scientist.

The team developed a modeling framework that predicts that the largest increase in cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms (CyanoHABs) would occur in the Northeast region of the United States, but the biggest economic harm would be felt by recreation areas in the Southeast.

>> Read the Full Article

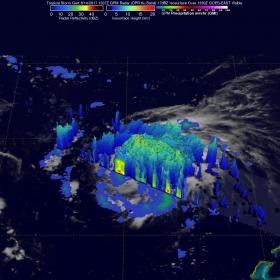

NASA looked at the rainfall rates within Tropical Storm Gert as it continued to strengthen and found the most intense rainfall on the tropical cyclone's eastern side. Just over 12 hours later, Gert would strengthen into a hurricane. As Gert has strengthened, the storm began generating dangerous surf along the U.S. East coast.

The Global Precipitation Measurement mission or GPM core observatory satellite passed above tropical storm Gert on August 14, 2017 at 9:36 a.m. EDT (1336 UTC) when winds had reached about 57.5 mph (50 knots). Data collected by GPM's Microwave Imager (GMI) and Dual-Frequency Precipitation Radar (DPR) instruments were used to show the coverage and the intensity of rainfall around Tropical Storm Gert. The area covered by GPM's radar swath revealed that the most intense rainfall, measuring greater 3.5 inches (90 mm) per hour, was located in bands of rain on the eastern side of the storm.

>> Read the Full Article

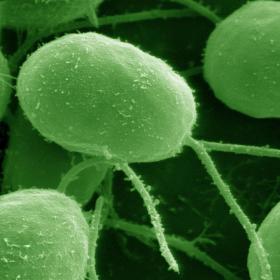

The mercury found at very low concentrations in water is concentrated along the entire food chain, from algae via zooplankton to small fish and on to the largest fish — the ones we eat. Mercury causes severe and irreversible neurological disorders in people who have consumed highly contaminated fish. Whereas we know about the element’s extreme toxicity, what happens further down the food chain, all the way down to those microalgae that are the first level and the gateway for mercury? By employing molecular biology tools, a team of researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, has addressed this question for the first time. The scientists measured the way mercury affects the gene expression of algae, even when its concentration in water is very low, comparable to European environmental protection standards. Find out more about the UNIGE research in Scientific Reports.

>> Read the Full Article

ENN

Environmental News Network -- Know Your Environment

ENN

Environmental News Network -- Know Your Environment