During a power outage in California in the 1990s, alarmed residents reportedly called in to report a strange, cloudy shape in the nighttime sky. It turned out to be the Milky Way- seen for the first time. For those of us who live in urban or suburban areas, an overabundance of artificial nighttime light, or light pollution, is nothing new. But light pollution isn't just a bane to astronomers and an annoyance to the rest of us: studies show that it also poses real health risks, including some increased rates of cancer.

During a power outage in California in the 1990s, alarmed residents reportedly called in to report a strange, cloudy shape in the nighttime sky. It turned out to be the Milky Way- seen for the first time. For those of us who live in urban or suburban areas, an overabundance of artificial nighttime light, or light pollution, is nothing new. But light pollution isn't just a bane to astronomers and an annoyance to the rest of us: studies show that it also poses real health risks, including some increased rates of cancer.

A recent study done in Israel headed by Richard Stevens, a professor and cancer epidemiologist at the University of Connecticut Health Center, and published in Chronobiology International, has shown some disturbing trends between women exposed to large amounts of artificial night light and breast cancer.

Stevens' team overlaid satellite photos to measure nighttime artificial light levels with a map detailing the distribution of breast cancer cases. Those women living in the brightest areas (as defined by being able to read at outdoors at midnight) had a 73% higher risk of developing breast cancer than those living in areas with the least outdoor lighting.

These results correlate with an earlier study done in 2005 that showed women who worked night shifts in hospitals also had higher incidences of breast cancer. The report, published in Cancer Research, suggests that melatonin-or rather the lack of it-may be the cause. Melatonin is an essential hormone that our bodies make at night while we sleep. It requires darkness and plays a critical role in regulating our internal clocks. For women, the light-sensitive hormone is particularly important since scientists suspect that melatonin helps to reduce estrogen levels-higher estrogen levels being a factor in developing breast cancer. And melatonin levels drop precipitously in the presence of artificial light.

This research helps to explain two stark facts that epidemiologists have long known: breast cancer rates are three to five times higher in industrialized countries and, that breast cancer rates are 20 to 50 percent less in blind women.

Furthermore, a study released in February by University of Haifa researchers, found elevated risks of prostate cancer in countries with the highest levels of artificial light.

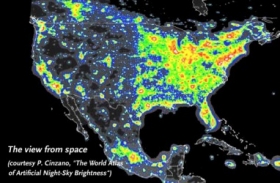

The most recent data on the amount of world light pollution was compiled in 1997 by Dr. Pierantonio Cinzano, in the First World Atlas of Artificial Night Brightness Health. In areas where 97% of the US population, 96% of the European Union population, and half of the world's population live, the sky is always at least as bright as it is when there is a half moon; for many others, "night" doesn't really come at all and the nighttime sky is in a perpetual twilight state. And, as for the Milky Way, more than two-thirds of Americans and half of all Europeans cannot see it with the naked eye.

In this country, the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) in Tucson, Arizona, estimates that $1.7 billion is wasted each year by unnecessary or excessive lighting, which is poorly designed and consequently misdirected into the sky. Wasted lighting releases 38 million tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere annually.

Although many communities are taking proactive steps to reduce light pollution, it remains a struggle, says Johanna Duffek, IDA's section coordinator and community liaison.

"When cities bring up Dark-Sky friendly regulations, citizens often assume this means turning off the lights," she explains. "IDA is not anti-light. We are pro-quality lighting. This is a very important distinction. Dark-Sky friendly lighting is safer than most existing lighting because it points the light on the ground where it is needed, not into the sky where it is not needed."

Eighteen states have instituted light pollution ordinances and, although they differ in range and in scope, they all contain, at the very least, provisions for outdoor, non-residential lighting. The IDA advocates using fully shielded lighting, which means no light above the 90 degree angle, and have a maximum lamp wattage of 250 watts for commercial lighting, 100 watts incandescent, and 26 watts compact florescent for residential lighting.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

The New England Light Pollution Advisory Group (NELPAG) , a volunteer group founded in 1993, helped Connecticut pass the most sweeping regulations in New England. Besides more shielded streetlights, communities are dimming their lights, changing them or, in some cases, turning them off completely. Last month, local officials in Groton, Massachusetts voted to turn off 199 of the town's 719 streetlights. The Long Island Power Authority has replaced hundreds of floodlights at its operating yards with full cut-off fixtures. Kansas is taking action due to complaints from military personnel that issues such as glare and light trespass (light from neighboring sources) were impeding night vision training. In Boston, participating building owners and managers are turning off or dimming architectural and internal lights between 11 p.m. and 5 a.m. during the spring migratory bird season which ends on May 31st.

Seventeen states and several countries have light pollution laws. In Canada, the city of Calgary replaced all 37,500 streetlights with more efficient ones, saving around $2 million a year.

Flagstaff, Arizona, has the distinction of being the world's first certified International Dark-Sky Community. However, even before this designation, Flagstaff has been working to reduce light pollution in the community for many years now - 50, to be exact. In 1958, astronomers at Lowell Observatory were adding a new telescope. They appealed to the city government and the first light pollution ordinance was passed banning searchlights. In 1989, the city went even further, adopting the strictest provisions in the world by restricting light to a specific number of lumens per acre, based on proximity to the Observatory.

"We decided to become a certified dark-sky city mainly to get people to notice it," says John Grahame, the Program Coordinator for the Coconino County Sustainable Economic Development Initiative. "It's on a sign when you drive into the city and people are curious and ask about it."

Grahame, who is also President of the Flagstaff Dark Skies Coalition, works with local businesses to help reduce their light pollution. He hopes when visitors can see he stars in Flagstaff is, they'll want to do improve their own communities.

"Flagstaff is a beautiful place and our dark skies are a huge part of its beauty," he says. "Even our Taco Bell is gorgeous."

This article is reproduced with kind permission of the

Organic Consumers Association.

For more news and articles, visit www.organicconsumers.org.