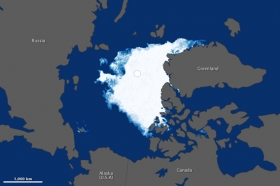

This year saw the Arctic sea ice extent fall to a new and shocking low, while the U.S. experienced it warmest month ever on record (July), beating even Dust Bowl temperatures. Meanwhile, a flood of new research has convincingly connected a rise in extreme weather events, especially droughts and heatwaves, to global climate change, and a recent report by the DARA Group and Climate Vulnerability Forum finds that climate change contributes to around 400,000 deaths a year and costs the world 1.6 percent of its GDP, or $1.2 trillion. All this and global temperatures have only risen about 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.44 degrees Fahrenheit) since the early Twentieth Century. Scientists predict that temperatures could rise between 1.1 degrees Celsius (2 degrees Fahrenheit) to a staggering 6.4 degrees Celsius (11.5 degrees Fahrenheit) by the end of the century.

This year saw the Arctic sea ice extent fall to a new and shocking low, while the U.S. experienced it warmest month ever on record (July), beating even Dust Bowl temperatures. Meanwhile, a flood of new research has convincingly connected a rise in extreme weather events, especially droughts and heatwaves, to global climate change, and a recent report by the DARA Group and Climate Vulnerability Forum finds that climate change contributes to around 400,000 deaths a year and costs the world 1.6 percent of its GDP, or $1.2 trillion. All this and global temperatures have only risen about 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.44 degrees Fahrenheit) since the early Twentieth Century. Scientists predict that temperatures could rise between 1.1 degrees Celsius (2 degrees Fahrenheit) to a staggering 6.4 degrees Celsius (11.5 degrees Fahrenheit) by the end of the century.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

Despite this, governments around the world have been slow to tackle climate change; global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise year-after-year. In many ways policies are going backwards: Germany, one of the world's greenest top economies, is looking at increasing its use of coal; Canada has abandoned the Kyoto Treaty and its government is fully committed to bringing its tar sands to a global market; big oil companies are now drilling in the melting Arctic for more fossil fuels; and the race for the U.S. presidency has had nary a mention of climate change. The lack of movement on the issue politically has meant that some scientists are looking toward other options to combat climate change once the damage becomes undeniable, including hugely-controversial geo-engineering ideas. But a recent study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) argues for a bold, and perhaps less dangerous approach than geo-engineering ideas: physically pull carbon out of the atmosphere.

"If climate change is quicker than expected, then the world has likely overshot the acceptable limit of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere or will go over before emissions can get stopped," Klaus Lackner, lead author of the paper with the Earth Institute at Colombia University and board member of atmospheric carbon-capturing company, Kilimanjaro Energy, told mongabay.com. "Unlike flue gas scrubbing [which removes emissions from power plants], air capture can remove more carbon dioxide than is emitted. Therefore, it can gradually reduce CO2 levels in the atmosphere; not overnight, but a lot faster than nature will do it by itself."

The big draw for capturing carbon from the atmosphere is that on a massive-scale it could theoretically turn the current situation around. Global society is now putting extra carbon into the atmosphere every year to the tune of around 30 billion metric tons, but air-based carbon capture on a large-scale could actually produce negative emissions by pulling more carbon out than is being emitted, and theoretically re-cool the planet a lot faster than waiting for current carbon emissions to leave the atmosphere naturally. Carbon can hang around in the atmosphere for centuries before being sequestered by the oceans or vegetation.

Article continues at ENN affiliate, Mongabay

Image credit: NASA