UCLA biologists have developed an intervention that serves as a cellular time machine — turning back the clock on a key component of aging.

UCLA biologists have developed an intervention that serves as a cellular time machine — turning back the clock on a key component of aging.

In a study on middle-aged fruit flies, the researchers substantially improved the animals’ health while significantly slowing their aging. They believe the technique could eventually lead to a way to delay the onset of Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, stroke, cardiovascular disease and other age-related diseases in humans.

The approach focuses on mitochondria, the tiny power generators within cells that control the cells’ growth and determine when they live and die. Mitochondria often become damaged with age, and as people grow older, those damaged mitochondria tend to accumulate in the brain, muscles and other organs. When cells can’t eliminate the damaged mitochondria, those mitochondria can become toxic and contribute to a wide range of age-related diseases, said David Walker, a UCLA professor of integrative biology and physiology, and the study’s senior author.

Read more at University of California - Los Angeles

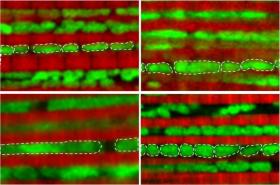

Image: Fruit flies' mitochondria (in green) at 10 days (top left), 28 days (top right) and 37 days old (both bottom images). At bottom right, the mitochondria have returned to a more youthful state after UCLA biologists increased the fly's level of a protein called Drp1. (Credit: Nature Communications/Anil Rana)