In a study led by Dr Jenny Zhang, a Research Associate at St John's, academics have found an unexpected performance-destructive pathway within Photosystem II, an enzyme at the heart of oxygenic photosynthesis, and one that is also being used to inspire new approaches to renewable fuel production.

>> Read the Full Article

A new study says that human-induced climate change has doubled the area affected by forest fires in the U.S. West over the last 30 years. According to the study, since 1984 heightened temperatures and resulting aridity have caused fires to spread across an additional 16,000 square miles than they otherwise would have—an area larger than the states of Massachusetts and Connecticut combined. The authors warn that further warming will increase fire exponentially in coming decades.

>> Read the Full Article

For the first time in history, a group of bees in the U.S. will be protected under the Endangered Species Act, following a recent announcement from wildlife officials.

The group of bees, who are commonly known as yellow-faced bees because of the markings on their faces, are endemic only to the Hawaiian islands. While there are dozens of species, scientists identified several of them who are at risk of extinction and have been calling for their protection for years.

>> Read the Full Article

A visible image showing powerful Hurricane Matthew and Nicole on Oct. 6 at 1 p.m. EDT was captured by NOAA's GOES-East satellite. The image shows large Hurricane Matthew's clouds stretching from eastern Cuba and Hispaniola, over the Bahamas and extending to Florida. Matthew is west of the much smaller Tropical Storm Nicole. The image was created at the NASA/NOAA GOES Project at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

>> Read the Full Article

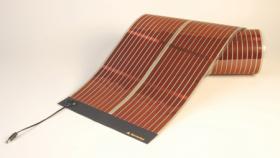

It was believed that efficient operation of organic solar cells requires a large driving force, which limits the efficiency of organic solar cells. Now, a large group of researchers led by Feng Gao, lecturer at IFM at LiU, He Yan at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and Kenan Gundogdu at the North Carolina State University have developed efficient organic solar cells with very low driving force.

This implies that the intrinsic limitations of organic solar cells are no greater than those of other photovoltaic technologies, bringing them a step closer to commercialisation.

>> Read the Full Article

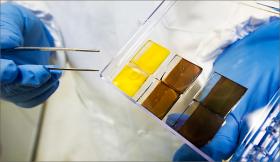

Scientists at Oxford University have developed a solvent system with reduced toxicity that can be used in the manufacture of perovskite solar cells, clearing one of the barriers to the commercialisation of a technology that promises to revolutionise the solar industry.

Perovskites – a family of materials with the crystal structure of calcium titanate – have been described as a 'wonder material' and shown to be almost as efficient as silicon in harnessing solar energy, as well as being significantly cheaper to produce.

>> Read the Full Article

ENN

Environmental News Network -- Know Your Environment

ENN

Environmental News Network -- Know Your Environment