New findings from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) provide the strongest evidence yet that liquid water flows intermittently on present-day Mars.

Using an imaging spectrometer on MRO, researchers detected signatures of hydrated minerals on slopes where mysterious streaks are seen on the Red Planet.

>> Read the Full Article

EPA today confirmed that New Englanders experienced a slight increase in the number of unhealthy air quality days this year, compared to 2014 and 2013.

Based on preliminary data collected between April and September 2015, there were 24 days when ozone monitors in New England recorded concentrations above levels considered healthy. By contrast, in 2014 there were a total of 9 unhealthy ozone days, and in 2013 there were a total of 20 such days.

The number of unhealthy ozone days in each state this summer is as follows:

- 22 days in Connecticut (compared to 8 in 2014, and 18 in 2013)

- 4 days in Rhode Island (0 in 2014, and 7 in 2013)

- 3 days in Massachusetts (0 in 2014, and 6 in 2013)

- 2 days in Maine (0 in 2014, and 5 in 2013)

- 2 days in New Hampshire (1 in 2014, and 3 in 2013)

- 0 days in Vermont (0 in both 2014, and 2013).

>> Read the Full Article

The revelations that Volkswagen, the world's second largest car manufacturer, had routinely gamed US emissions testing has thrown the spotlight on the environmental and health impact of cars.

While EU member states, such as the UK, open or consider investigations into the beleaguered company, European Commission officials are currently reviewing the executive’s 2011 White Paper for transport, its main policy roadmap for the sector.

Bringing extra impetus to their deliberation is the upcoming UN Climate Change Conference in Paris, international talks aimed at capping global warming.

>> Read the Full Article

Offshore wind farms which are to be built in waters around the UK could pose a greater threat to protected populations of gannets than previously thought, research led by the University of Leeds says.

It was previously thought that gannets, which breed in the UK between April and September each year, generally flew well below the minimum height of 22 metres above sea level swept by the blades of offshore wind turbines.

>> Read the Full Article

A start-up business focused on finding new ways of using insect protein in food products is a finalist in this year’s MassChallenge, the Boston-based start-up competition and world’s largest accelerator program. Get over your squeamishness, because bug-based foods will soon infest our markets.

The “elevator pitch” for Israel-based The Flying Spark states their intent to manufacture protein powder based on insect larvae that can be added to a wide range of food products, replacing today’s protein powders – commonly made from whey, soy, or casein. Insects contain extremely high protein, fiber, micro-nutrients and mineral content. They’re also naturally low in fat, and cholesterol-free. The tipping point for this product’s potential is that insect protein will cost less to produce than any other source of animal protein.

>> Read the Full Article

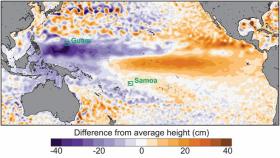

Many tropical Pacific island nations are struggling to adapt to gradual sea level rise stemming from warming oceans and melting ice caps. Now they may also see much more frequent extreme interannual sea level swings. The culprit is a projected behavioral change of the El Niño phenomenon and its characteristic Pacific wind response, according to recent computer modeling experiments and tide-gauge analysis by scientists Matthew Widlansky and Axel Timmermann at the International Pacific Research Center, University of HawaiÊ»i at MÄnoa, and their colleague Wenju Cai at Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) in Australia.

During El Niño, warm water and high sea levels shift eastward, leaving in their wake low sea levels in the western Pacific. Scientists have already shown that this east-west seesaw is often followed six months to a year later by a similar north-south sea level seesaw with water levels dropping by up to one foot (30 cm) in the Southern Hemisphere. Such sea level drops expose shallow marine ecosystems in South Pacific Islands, causing massive coral die-offs with a foul smelling tide called taimasa (pronounced [kai’ ma’sa]) by Samoans.

>> Read the Full Article

Horses need help when it comes to insect pests like flies. But, unfortunately, horse owners are in the dark about how best to manage flies because research just hasn't been done, according to a new overview of equine fly management in the latest issue of the Journal of Integrated Pest Management, an open-access journal that is written for farmers, ranchers, and extension professionals.

>> Read the Full Article

ENN

Environmental News Network -- Know Your Environment

ENN

Environmental News Network -- Know Your Environment