WASHINGTON (Reuters) - U.S. researchers have cloned monkeys and used the resulting embryos to get embryonic stem cells, an important step towards being able to do the same thing in humans, they reported on Wednesday.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov and colleagues at Oregon Health & Science University said they used skin cells from monkeys to create cloned embryos, and then extracted embryonic stem cells from these days-old embryos.

This had only been done in mice before, they reported in the journal Nature. Mitalipov had given sketchy details of his work at a conference in Australia in June, but the work has now been independently verified by another team of experts.

By Maggie Fox, Health and Science Editor

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - U.S. researchers have cloned monkeys and used the resulting embryos to get embryonic stem cells, an important step towards being able to do the same thing in humans, they reported on Wednesday.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov and colleagues at Oregon Health & Science University said they used skin cells from monkeys to create cloned embryos, and then extracted embryonic stem cells from these days-old embryos.

This had only been done in mice before, they reported in the journal Nature. Mitalipov had given sketchy details of his work at a conference in Australia in June, but the work has now been independently verified by another team of experts.

They said their work shows it is possible, in principle, to clone humans and get stem cells from the embryos. "The efficiency is still low but I am quite sure that it will work in humans," Mitalipov told reporters in a telephone briefing.

Embryonic stem cells are the source of every cell, tissue and organ in the body. Scientists study them to understand the biology of disease and want to use them to transform medicine.

The idea would be to take a small piece of skin from a patient and grow tissue or even organ transplants perfectly matched to the patient.

But their use is controversial, with opponents saying it is wrong to use a human embryo in this way. President George W. Bush has repeatedly blocked legislation that would expand federal funding of such research.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

OVERCOMING BARRIERS

Many species of animals have been cloned, and experts have taken stem cells from a variety of embryos, including human embryos. But it has been very difficult to both clone and then get embryonic stem cells from any animal.

Mitalipov's team overcame two barriers -- first cloning a primate, the group of mammals that includes monkeys, apes and humans, and then getting embryonic stem cells from the clone.

Mitalipov said the dyes used in cloning some animals apparently are toxic to primate cells.

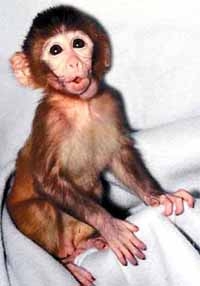

They used somatic cell nuclear transfer, which involves taking the nucleus from an adult cell, in this case fibroblasts, a type of skin cell, taken from nine adult males.

Then an egg cell is hollowed out and the nucleus from the adult cell inserted. This programs the egg into behaving as if it had been fertilized and it can grow into a embryo.

It was not easy. The researchers used 304 eggs from 14 rhesus macaque monkeys and ended up with just two stem cell lines.

This means a lot more work before this would be useful for humans, they said -- especially given how hard human eggs are to come by.

Tests show the embryonic stem cells are truly pluripotent, Mitalipov said, meaning they can develop into any kind of cell found in the body.

"We have been able to develop them into heart cells," he said. They also grew nerve cells.

It was important to confirm the work. A rival journal, Science, was forced to withdraw papers published by South Korean scientist Hwang Woo-suk in 2004 and 2005 after his claims to have cloned a human embryo proved false.

Mitalipov said the team has tried, and failed, to produce cloned monkeys that could grow into live baby monkeys.

"We have a goal also of producing live monkeys using the somatic cell nuclear transfer technique," he said. "One reason is to generate genetically modified macaques that, for example, carry a specific disease that is a model of human disease."

His team will not try to clone humans, he said.

"However we hope the techniques we develop will be useful for other labs which are working ... with human eggs," he said.

(Editing by Julie Steenhuysen and Cynthia Osterman)