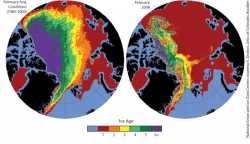

More than half of the Arctic Ocean was covered in year-round ice in the mid-1980s. Today, the ice cap is much smaller. Alarming evidence of this warming trend was released last week when the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) released satellite evidence that perennial Arctic ice cover, as of February, rests on less than 30 percent of the ocean. "The rate of sea-ice loss we're observing is much worse than even the most pessimistic projections led us to believe," says Carroll Muffett, deputy campaigns director with Greenpeace USA. For the first time in recorded history, this past summer the entire Northwest Passage between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans was ice-free, according to scientists.

More than half of the Arctic Ocean was covered in year-round ice in the mid-1980s. Today, the ice cap is much smaller. Alarming evidence of this warming trend was released last week when the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) released satellite evidence that perennial Arctic ice cover, as of February, rests on less than 30 percent of the ocean.

"The rate of sea-ice loss we're observing is much worse than even the most pessimistic projections led us to believe," says Carroll Muffett, deputy campaigns director with Greenpeace USA. For the first time in recorded history, this past summer the entire Northwest Passage between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans was ice-free, according to scientists.

In the eyes of oil and gas companies, like U.S-based Arctic Oil & Gas Corp., these open waters are potential treasure chests. As the Arctic Ocean resembles less like a gigantic ice sheet and more an ocean of frigid water, energy companies are racing to profit from the melting sea.

Arctic Oil & Gas Corp., an exploration company, has claimed exclusive rights to develop oil resources in the Arctic Ocean. On Tuesday, the group invited major companies from Canada, Norway, and Denmark to explore the Arctic abyss. "It simply doesn't get any bigger than this in the oil patch," CEO Peter Sterling said in a statement.

!ADVERTISEMENT!

However, Arctic Oil & Gas Corp. does not yet have official rights to its claim. Development rights in the Arctic Ocean are heavily disputed between the United States, Russia, Canada, and Norway. All four countries are debating how far their continental shelf extends into the ocean and therefore grants them rights to drill. "We're like Lewis and Clark, exploring an area that could significantly increase the area of the U.S.," said David Balton, the U.S. State Department's deputy assistant secretary for oceans and fisheries.

But the potential is still unknown. Modern technology has not accurately assessed the magnitude of oil or gas reserves below the polar caps, Balton said.

In the seas north of Russia and Alaska, expanded oil-and-gas development is already under way. The U.S. Department of Interior last month sold a record-breaking $2.6 billion in development bids throughout the Chukchi Sea, just above the Bering Strait. Additional sales are scheduled for 2010 and 2012.

As companies move into the Arctic to search for energy reserves or to create new shipping lanes, the potential environmental impacts could be huge. Balton acknowledged that shifting ice and coastal erosion makes exploration and development risky. "It's definitely a dangerous area to maneuver. An oil spill would be really hard to clean up," he said.

A report issued by the Interior Department's Minerals Management Service said that in addition to possible damage from lengthy pipelines and onshore facilities construction, "commenters expressed attendant concerns about the inability to clean up an oil spill in broken-ice conditions."

Polar bears, now threatened due to climate change, would face further stress if the Arctic is developed, due to increased contact with humans, Greenpeace's Muffett said.

Some environmentalists argue that the proposal to list the polar bear as threatened on the Endangered Species Act has been delayed to allow the Chukchi drilling plans to continue.

Ben Block is a staff writer at the Worldwatch Institute who covers everything environmental for Eye on Earth. He can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..