Two new studies by researchers at the University of California, Irvine and NASA have found the fastest ongoing rates of glacier retreat ever observed in West Antarctica and offer an unprecedented look at ice melting on the floating undersides of glaciers. The results highlight how the interaction between ocean conditions and the bedrock beneath a glacier can influence the frozen mass, helping scientists better predict future Antarctica ice loss and global sea level rise.

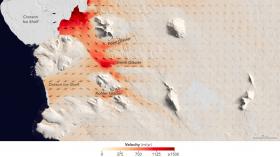

The studies examined three neighboring glaciers that are melting and retreating at different rates. The Smith, Pope and Kohler glaciers flow into the Dotson and Crosson ice shelves in the Amundsen Sea embayment in West Antarctica, the part of the continent with the largest decline in ice.

Two new studies by researchers at the University of California, Irvine and NASA have found the fastest ongoing rates of glacier retreat ever observed in West Antarctica and offer an unprecedented look at ice melting on the floating undersides of glaciers. The results highlight how the interaction between ocean conditions and the bedrock beneath a glacier can influence the frozen mass, helping scientists better predict future Antarctica ice loss and global sea level rise.

The studies examined three neighboring glaciers that are melting and retreating at different rates. The Smith, Pope and Kohler glaciers flow into the Dotson and Crosson ice shelves in the Amundsen Sea embayment in West Antarctica, the part of the continent with the largest decline in ice.

“Our primary question is how the Amundsen Sea sector of West Antarctica will contribute to sea level rise in the future, particularly following our observations of massive changes in the area over the last two decades,” said UCI’s Bernd Scheuchl, lead author on the first of the two studies, published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters in August.

“Using satellite data, we continue to measure the evolution of the grounding line of these glaciers, which helps us determine their stability and how much mass the glacier is gaining or losing,” said the Earth system scientist. “Our results show that the observed glaciers continue to lose mass and thus contribute to global sea level rise.”

Continue reading at the University of California, Irvine

Image via NASA JPL