As scientists work to predict how climate change may affect hurricanes, droughts, floods, blizzards and other severe weather, there's one area that's been overlooked: mild weather. But no more.

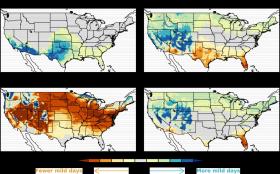

NOAA and Princeton University scientists have produced the first global analysis of how climate change may affect the frequency and location of mild weather - days that are perfect for an outdoor wedding, baseball, fishing, boating, hiking or a picnic. Scientists defined "mild" weather as temperatures between 64 and 86 degrees F, with less than a half inch of rain and dew points below 68 degrees F, indicative of low humidity.

As scientists work to predict how climate change may affect hurricanes, droughts, floods, blizzards and other severe weather, there's one area that's been overlooked: mild weather. But no more.

NOAA and Princeton University scientists have produced the first global analysis of how climate change may affect the frequency and location of mild weather - days that are perfect for an outdoor wedding, baseball, fishing, boating, hiking or a picnic. Scientists defined "mild" weather as temperatures between 64 and 86 degrees F, with less than a half inch of rain and dew points below 68 degrees F, indicative of low humidity.

Knowing the general pattern for mild weather over the next decades is also economically valuable to a wide range of businesses and industries. Travel, tourism, construction, transportation, agriculture, and outdoor recreation all benefit from factoring weather patterns into their plans.

Tropics to lose milder days

The new research, published in the journal Climatic Change, projects that globally the number of mild days will decrease by 10 or 13 percent by the end of the century because of climate warming from the buildup of human-caused greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The current global average of 74 mild days a year will drop by four days by 2035 and 10 days by 2081 to 2100. But this global average decrease masks more dramatic decreases in store for some areas and increases in mild days in other regions.

"Extreme weather is difficult to relate to because it may happen only once in your lifetime," said first author Karin van der Wiel, a Princeton postdoctoral researcher at NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) located on the university's Forrestal Campus. "We took a different approach here and studied a positive meteorological concept, weather that occurs regularly, and that's easier to relate to."

Continue reading at EurekAlert!

IMAGE CREDIT: KARIN VAN DER WIEL/ NOAA/ PRINCETON