California’s winter rains and snow depress the Sierra Nevada and Coast Ranges, which then rebound during the summer, changing the stress on the state’s earthquake faults and causing seasonal upticks in small quakes, according to a new study by University of California, Berkeley seismologists.

The weight of winter snow and stream water pushes down the Sierra Nevada mountains by about a centimeter, or three-eighths of an inch, while ground and stream water depress the Coast Ranges by about half that. This loading and the summer rebound – the rise of the land after all the snow has melted and much of the water has flowed downhill – makes the earth’s crust flex, pushing and pulling on the state’s faults, including its largest, the San Andreas.

California’s winter rains and snow depress the Sierra Nevada and Coast Ranges, which then rebound during the summer, changing the stress on the state’s earthquake faults and causing seasonal upticks in small quakes, according to a new study by University of California, Berkeley seismologists.

The weight of winter snow and stream water pushes down the Sierra Nevada mountains by about a centimeter, or three-eighths of an inch, while ground and stream water depress the Coast Ranges by about half that. This loading and the summer rebound – the rise of the land after all the snow has melted and much of the water has flowed downhill – makes the earth’s crust flex, pushing and pulling on the state’s faults, including its largest, the San Andreas.

The researchers can measure these vertical motions using the regional global positioning system and thus calculate stresses in the earth due the water loads. They found that on average, the state’s faults experienced more small earthquakes when these seasonal stress changes were at their greatest.

Continue reading at University of California – Berkeley

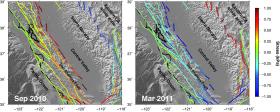

Image: In 2010, the San Andreas fault (left image, red and orange lines) experienced peak stress in September after snowmelt and runoff allowed the mountains to rebound. Faults east of the Sierra Nevada (right, red and orange) experienced peak stress in March of the following year. Credits: Christopher Johnson, Berkeley Seismological Laboratory, UC Berkeley