UC San Diego researchers have settled a decades-long debate surrounding the role of the first Crohn’s disease gene to be associated with a heightened risk for developing the auto-immune condition.

UC San Diego researchers have settled a decades-long debate surrounding the role of the first Crohn’s disease gene to be associated with a heightened risk for developing the auto-immune condition.

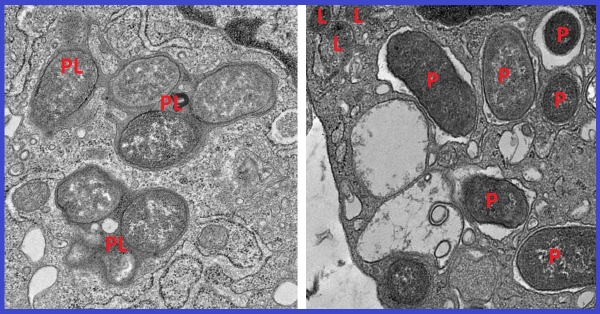

The human gut contains two types of macrophages, or specialized white blood cells, that have very different but equally important roles in maintaining balance in the digestive system. Inflammatory macrophages fight microbial infections, while non-inflammatory macrophages repair damaged tissue. In Crohn’s disease — a form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) — an imbalance between these two types of macrophages can result in chronic gut inflammation, damaging the intestinal wall and causing pain and other symptoms.

Researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine have developed a new approach that integrates artificial intelligence (AI) with advanced molecular biology techniques to decode what determines whether a macrophage will become inflammatory or non-inflammatory.

The study also resolves a longstanding mystery surrounding the role of a gene called NOD2 in this decision-making process. NOD2 was discovered in 2001 and is the first gene linked to a heightened risk for Crohn’s disease.

Read More: University of California – San Diego

Image: Electron micrographs show how macrophages expressing girdin neutralize pathogens by fusing phagosomes (P) with the cell’s lysosomes (L) to form phagolysosomes (PL), compartments where pathogens and cellular debris are broken down (left). This process is crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis. In the absence of girdin, this fusion fails, allowing pathogens to evade degradation and escape neutralization (right). (UC San Diego Health Sciences)