The environmental impact of your Thanksgiving dinner depends on where the meal is prepared.

Carnegie Mellon University researchers calculated the carbon footprint of a typical Thanksgiving feast – roasted turkey stuffed with sausage and apples, green bean casserole and pumpkin pie – for each state. The team based their calculations on the way the meal is cooked (gas versus electric range), the specific state’s predominant power source and how the food is produced in each area.

They found that dinners cooked in Maine and Vermont, states that rely mostly on renewable energy, emit the lowest amounts of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that is tied to climate change. States that use coal power, such as Wyoming, West Virginia and Kentucky, have the highest carbon dioxide emissions.

>> Read the Full Article

If society continues to pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere at the current rate, Americans later this century will have to endure, on average, about 15 daily maximum temperature records for every time that the mercury notches a record low, new research indicates.

That ratio of record highs to record lows could also turn out to be much higher if the pace of emissions increases and produces even more warming, according to the study led by scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

>> Read the Full Article

In large parts of Europe and North America, the decline in industrial emissions over the past 20 years has reduced pollution of the atmosphere and in turn of soils and water in many natural areas. The fact that this positive development can also have negative implications for these regions has been demonstrated by scientists at the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) in the journal Global Change Biology. According to their findings, declining nitrate concentrations in the riparian soils surrounding the tributary streams of reservoirs are responsible for the increasing release of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and phosphate and a deterioration in water quality. In the case of drinking water reservoirs this can cause considerable problems with respect to water treatment.

>> Read the Full Article

Climate change is one of the most serious threats facing the world today. With the effectuation of the Paris Agreement, there has been a rising interest on carbon capture and utilization (CCU).

A new study, led by Professor Jae Sung Lee of Energy and Chemical Engineering at UNIST uncovers new ways to make biofuel from carbon dioxide (CO2), the most troublesome greenhouse gas. In their paper published in the journal Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, the team presented direct CO2 conversion to liquid transportation fuels by reacting with renewable hydrogen (H2) generated by solar water splitting.

>> Read the Full Article

Half of all coral species in the Caribbean went extinct between 1 and 2 million years ago, probably due to drastic environmental changes. Which ones survived? Scientists working at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) think one group of survivors, corals in the genus Orbicella, will continue to adapt to future climate changes because of their high genetic diversity.

“Having a lot of genetic variants is like buying a lot of lottery tickets,” said Carlos Prada, lead author of the study and Earl S. Tupper Post-doctoral Fellow at STRI. “We discovered that even small numbers of individuals in three different species of the reef-building coral genus Orbicella have quite a bit of genetic variation, and therefore, are likely to adapt to big changes in their environment.”

>> Read the Full Article

Rudy Boonstra has been doing field research in Canada’s north for more than 40 years.

Working mostly out of the Arctic Institute’s Kluane Lake Research Station in Yukon, the U of T Scarborough biology professor has become intimately familiar with Canada’s vast and unique boreal forest ecosystem.

But it was during a trip to Finland in the mid-1990s to help a colleague with field research that he began to think long and hard about why the boreal forest there differed so dramatically from its Canadian cousin. This difference was crystallized by follow-up trips to Norway.

>> Read the Full Article

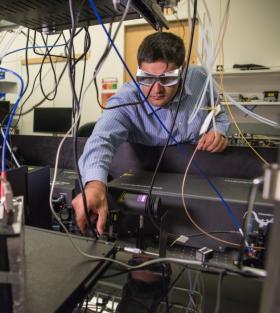

Next-generation solar cells made of super-thin films of semiconducting material hold promise because they’re relatively inexpensive and flexible enough to be applied just about anywhere.

Researchers are working to dramatically increase the efficiency at which thin-film solar cells convert sunlight to electricity. But it’s a tough challenge, partly because a solar cell’s subsurface realm—where much of the energy-conversion action happens—is inaccessible to real-time, nondestructive imaging. It’s difficult to improve processes you can’t see.

Now, scientists from the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have developed a way to use optical microscopy to map thin-film solar cells in 3-D as they absorb photons.

>> Read the Full Article

Heartbreaking stories of seabirds eating plastic — and the accompanying horrible images— are everywhere, but now scientists are an important question: Why do seabirds eat plastic in the first place? And why are some more likely to have bellies full of plastic than others?

The answer, it turns out, lies in a compound called dimethyl sulfide, or DMS, which emits a “chemical scream” that some birds associate with food. When seabirds find chunks of plastic bobbing in the water, they gobble them up, not realizing that they’ve just consumed something very dangerous.

>> Read the Full Article

ENN

Environmental News Network -- Know Your Environment

ENN

Environmental News Network -- Know Your Environment